My checkup visit to the doctor went south in a hurry after my doctor measured my pulse and declared, ‘Todd, go to hospital emergency right away. Your heart is fluttering.’

By Todd Etshman

My primary care’s English isn’t perfect, but we work it out.

At times, the India native doctor asks me how to spell something during the four and a half minutes that her health care company’s bosses allocate for checkups.

I’ve been meaning to ask her where I should go for a prostate check since my PSA is on a slow-moving up escalator. I’m pretty sure she isn’t keen to do it. But we had other problems to face on this visit.

I hadn’t been feeling great before my last appointment. Another round of COVID-19 followed by a severe respiratory infection plagued me in the months following the new year.

Even when those afflictions were gone, I found I couldn’t get my running or fitness strength back. I couldn’t go half a mile before feeling like I had to stop. Friends and acquaintances said it just took a long time to come back and it had happened to others, too, in the age of COVID-19 and SARS.

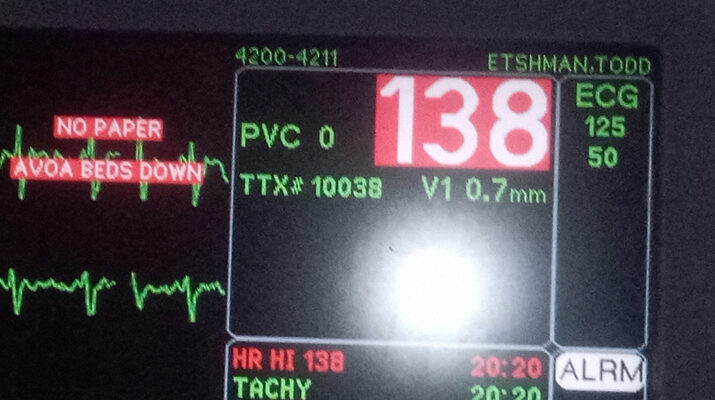

But this checkup visit went south in a hurry when my doctor measured my pulse and declared, “Todd, go to hospital emergency right away. Your heart is fluttering.”

Then she left the room and headed back to her office. Incredulous, I stopped her in the hallway and asked if that was really necessary and could I go another day since I had a host of things to do.

She said something like, “No, you go now. I’ll call ahead — they’ll be waiting for you.”

And they were. My pulse was in the 150 beats per minute range and as it turned out, it had been for months.

The next thing I knew I was being led to a private room in Rochester General Hospital emergency past people who looked decidedly worse off than me. People with horrible wounds and health issues lined the hallways outside my room.

The elderly woman outside my room seemed perilously close to death’s door. Benevolence may not come easy to me, but I wanted her to have my room. But for whatever reason, that wasn’t happening.

Quickly, a team of nurses and specialists started their work. The first cardiologist I saw asked if I’d ever run a marathon because my heart had done the equivalent of a marathon a day for weeks on end.

He also said without my lifelong commitment to fitness, I probably would not have made it since the human heart isn’t made to keep going at 150 beats a minute for an extended period of time.

He also thought that COVID-19 and the respiratory illness could be to blame. After recuperating, he said, the heart just didn’t get the message to ease up and it kept on going.

The anti-vaccinators in my family were sure it was the vaccine’s fault and that Robert Kennedy Jr.’s vaccine warning is absolutely not to be taken lightly.

Whatever caused it, however, didn’t matter as much as fixing it.

Quickly, I was placed on medications such as Metoprolol. I was supposed to be on Eliquis, a blood thinner, too, before having a TEE test but somehow that didn’t happen so my TEE test was postponed.

The explanation I received regarding the heart flutter was that the heart would be shocked to get it down to speed again. And, if that didn’t work…well, that wouldn’t be good, at all.

I was at risk for a stroke or a heart attack.

Meanwhile, I just felt a little tired, nothing else and watched the New York Rangers on television and ate pizza with the night nurse.

The transesophageal echocardiogram test (TEE) was being performed to see if thickened blood was coagulating around the heart and what, if anything, else was going on. But, getting the TEE test was difficult the second time around, too, when the computers malfunctioned and had to be replaced.

This time, they left me there to wait it out while the computer tech team got the computers hooked up. When I awoke a team of cardiologists that looked like something out of The Matrix, was there at my bedside to give me the mostly good news. Later, one of the young female cardiologists fell over my phone charge cord in the small, cramped room but opted to keep going.

Fortunately, the TEE test looked good and the shock to the heart brought the beat down but there was some residual effect that may or may not go away, my heart wasn’t pumping blood around completely as it should.

It may have been weakened. A marathon per day will do that. After that, I still couldn’t go home.

That would have to wait a day. When the beat looked consistently lower, I was released.

The next step is a follow-up visit with a cardiologist and another TEE test. I should have made that appointment by now but it doesn’t help that whatever call center the cardiologists use, has dropped my call three times. Call me, if you’re a cardiologist in Irondequoit with a staff that can make appointments.

And, while self-diagnosis is not recommended, once I could run a couple miles without laboring, I had a feeling I was OK. By then, my prostate PSA was high and I had to focus on the next medical challenge: a prostate biopsy. But I’ll save that for another time.